In a recent post on the Dabbler blog, Nige celebrated the rebirth of the little River Wandle, now running fresh and clear through Sutton, Merton and Wandsworth after more than a century of neglect:

Industrialisation had long since transformed what was once a sparkling chalk stream, famous for its plump brown trout, into one of the most comprehensively polluted waterways on earth. And yet today the water is again clean and clear and the trout are back . . . The Wandle sparkles and teems with life again, and the passing years have, for once, brought nothing but improvement – though the habit of dumping litter and other detritus in the river remains stubbornly persistent. Every prospect pleases, and only man is vile . . .

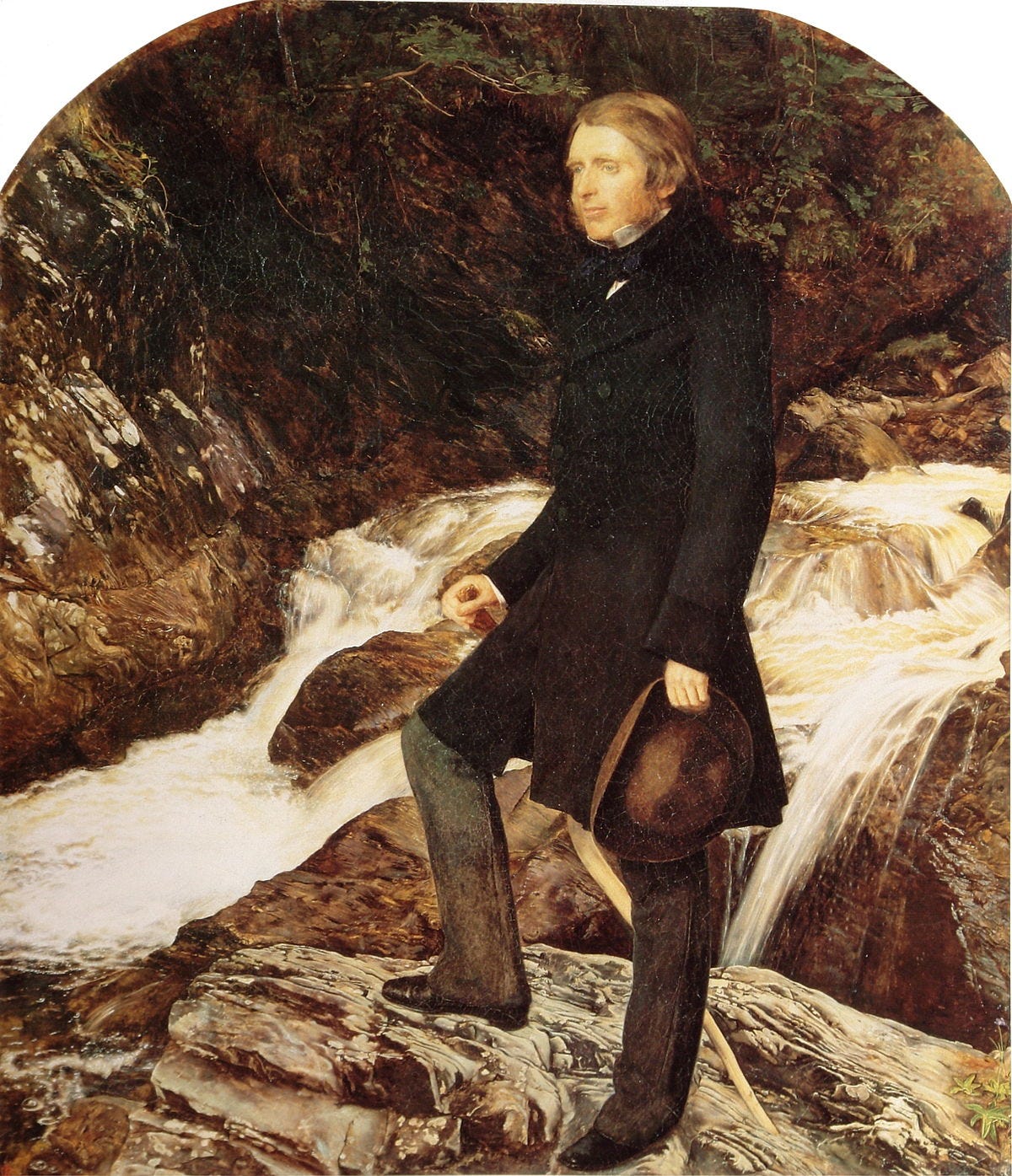

This rejuvenation would have delighted no one more than the great John Ruskin, who grieved fiercely for the Wandle in his once widely read polemic The Crown of Wild Olive. Here, in one of his great rhetorical set pieces, Ruskin contrasts the sorry state of the river in 1870 with the idyllic stream he remembered from earlier, preindustrial days. In a series of rapt, luminous paragraphs, the fringes of South London – where Ruskin had spent most of his rather odd childhood – take on the hues of an earthly paradise:

Twenty years ago, there was no lovelier piece of lowland scenery in South England . . . . than that immediately bordering on the sources of the Wandle, and including the lower moors of Addington, and the villages of Beddington and Carshalton, with all their pools and streams. No clearer or diviner waters ever sang with constant lips of the hand which ‘giveth rain from heaven’; no pastures ever lightened in spring time with more passionate blossoming …

It could almost be a scene from Samuel Palmer’s Valley of Vision – some 12 or 15 miles away across the rooftops of Bromley and Orpington. But then comes the horror of the Fall:

Just where the welling of stainless water, trembling and pure, like a body of light, enters the pool of Carshalton, cutting itself a radiant channel down to the gravel, through warp of feathery weeds, all waving, which it traverses with its deep threads of clearness, like the chalcedony in moss-agate, starred here and there with white grenouillette; just in the very rush and murmur of the first spreading currents, the human wretches of the place cast their street and house foulness; heaps of dust and slime, and broken shreds of old metal, and rags of putrid clothes; they having neither energy to cart it away, nor decency enough to dig it into the ground, thus shed into the stream, to diffuse what venom of it will float and melt, far away, in all places where God meant those waters to bring joy and health . . .

With deliberate mind I say, that I have never seen anything so ghastly in its inner tragic meaning . . . as the slow stealing of aspects of reckless, indolent, animal neglect, over the delicate sweetness of that English scene: nor is any blasphemy or impiety –any frantic saying or godless thought – more appalling to me . . . than the insolent defilings of those springs by the human herds that drink of them.

On one level, the ‘inner tragic meaning’ of this is quite straightforward: the poor, polluted Wandle is an emblem of English life, once sweet and clear and true but now tainted by commerce and the reckless pursuit of Mammon. Moreover, the economic orthodoxy of the day – a crude and dogmatic laissez-faire – means that no one can halt the ‘insolent defiling’ of these waters or take any concerted steps to put things right:

Half-a-dozen men, with one day’s work, could cleanse those pools, and trim the flowers about their banks, and make every breath of summer air above them rich with cool balm; and every glittering wave medicinal, as if it ran, troubled of angels, from the porch of Bethesda. But that day’s work is never given, nor will be; nor will any joy be possible to heart of man, for evermore, about those wells of English waters.

To this extent, the Wandle is more grist to Ruskin’s mill in his long quarrel with the ‘bastard science’ of political economy and the ethics of 19th-century capitalism. However, the sheer vehemence of the feeling and expression here (‘ghastly . . . blasphemy . . . wretches . . . venom’) suggests that something more private or personal is at stake: the ‘inner tragic meaning’ seems to need some outing.

So what’s it all about, really, this torrent of grief and rage? Firstly and most simply, I suppose, there’s the pang we all tend to feel at the loss of a childhood landscape, however ordinary or even dismal. To Ruskin the streams of Croydon, Norwood, and Carshalton sang of his early life and had particularly strong associations with his mother (in 1870 bedridden and near to death). Increasingly, it was in these leafy, well-watered scenes that he located the springs of his own moral character and vision. Writing in Praeterita, the great autobiography left unfinished at his death, he claimed that his ‘personal feeling and native instinct’ had been fastened irrevocably to ‘things modest, humble, and pure in peace' by the ‘low red roofs of Croydon’ – and by the ‘cress-set rivulets in which the sand danced and minnows darted above the Springs of Wandel.’

Likewise Ruskin traces the first stirrings of his artistic life to the streams of the Wandle basin, noting that his first sketch of any merit was inspired by the Effra – a tiny river long since obliterated. In a mordant aside, Ruskin links the name Effra to an old word meaning ‘unbridled’ before bringing us up to date: “recently . . . bricked over for the convenience of Mr Biffin, chemist”.

In an obscure, almost magical way, Ruskin seems to feel the rape of these little rivers as a threat to his own psyche – an assault on his deepest convictions about art, ethics, and society, as well as his dearest attachments. Magical thinking also appears to govern his intuition that a spring is a sacred place, and that the polluter of wells is guilty of a cosmic aggression against life itself.

As if to prove his point that a little work could make the difference – and to settle his fear that these ‘wells of English water’ were lost forever – in 1876 Ruskin set about cleansing one of the Carshalton springs as a memorial to his mother, Margaret. An inscribed tablet was placed above the fount:

In obedience to the Giver of Life, of the brooks and fruits that feed it, of the peace that ends it, may this well be kept sacred for the service of men, flocks, and flowers, and be by kindness called MARGARET’S WELL.

This pool was beautified and endowed by John Ruskin., M.A., LL.D.

Like Ruskin’s notorious road-building exploits at North Hinksey or his obsession with sweeping the streets outside the British Museum, this project was perhaps more important for its symbolic value than for any practical consequence. In this case, the results proved sadly short-lived. The clearing of the spring was a more difficult business than Ruskin had supposed and keeping it clean proved still more troublesome. The waters soon sickened and became foul and within a few years Ruskin’s tablet had also gone missing (it has now been recovered and may be seen in place).

The fable could easily end there, with Ruskin’s idealism exposed in all its folly and the Wandle continuing in its inevitable decline. But as we know, it turned out differently. Perhaps the natural world is always more resilient than we think. Perhaps Ruskin’s contemporary, Hopkins, had something right: ‘there lives the dearest freshness deep down things’.

This piece was originally posted on the Dabbler blog in July 2012, as part of a short series about John Ruskin and his fascination with rivers and irrigation. The other parts are: 2. Ruskin the Irrigationist and 3. The Water which Feeds the Roots of All Evil.

If you enjoyed this post, you might be interested in my ebook The Whartons of Winchendon — a short study of one of the strangest families in English history, featuring incest, treason, deep-sea diving, fairies, and the self-proclaimed Solar King of the World.