So far, this Phantom Library thing has been mostly for laughs. The libraries invented by Rabelais, Donne, Joyce, and Swift were all uproarious things, even where the humour seemed to be laced with something a bit uneasy (an anxiety about the state of writing and publishing in their time, perhaps; or more fundamentally, a worry about the whole literary enterprise itself). This week the mood shifts, as I go in quest of a different sort of literary ectoplasm – books that now exist only as dreams, rumours, and fragments; books written but now lost, or imagined but never written. Ribaldry shrivels into pathos, and any laughter is distinctly of the nervous kind . . .

Musaeum Clausum or Bibliotheca Abscondita (‘Sealed Museum or Secret Library’) is the title of a small tract that was found among the posthumous papers of Sir Thomas Browne – doctor, scientist, author, and antiquarian. Browne described his work as a catalogue of ‘remarkable books, antiquities, pictures and rarities of several kinds, scarce or never seen by any man now living’ – a summary that is wholly accurate, but does little to convey the spooked quality of this short meditation on time, loss, and the fragility of all human things. W. G. Sebald, who writes extensively about Browne in The Rings of Saturn, gets closer when he describes the Musaeum as ‘the inventory of a treasure house that existed purely in [Browne’s] head and to which there is no access except through the letters on the page’. But even that undersells its essential eeriness.

This week the mood shifts, as I go in quest of a different sort of literary ectoplasm – books that now exist only as dreams, rumours, and fragments; books written but now lost, or imagined but never written.

Browne’s catalogue of ‘rare and generally unknown books’ includes lost, rumoured, or fabled works by Aristotle, Democritus, Pythagoras, Galen, Caesar, Cicero, and King Alfred the Great. It’s an odd list, and one with a complicated flavour – a tone both melancholy and puckish. Some items sound like genuine classics, works that might have altered the whole landscape of Western culture – the tragedies of Diogenes the Cynic, poems written by Ovid during his exile at Tomos, the correspondence between St Paul and the Roman Stoic Seneca. Others sound implausible and even a bit mad, like something from the libraries of Donne or Rabelais (an account claiming that the great physician Avicenna died ‘by taking nine Clysters [enemas] together in a fit of the Colick’).

After three centuries, it’s still uncertain how far Browne was reporting genuine rumours, however wild, and how far he was making things up. Some of the most haunting items seem to be pure invention, notably a treatise by King Solomon on the shadows cast by our thoughts (as seen by a traveller in the library of the Duke of Bavaria). On the other hand, the account by one Pytheas, in which he describes a journey through Arctic realms where the air ‘is thick, condensed and gellied, looking just like Sea Lungs’ (apparently a type of jellyfish) turns out be historical – if known only from the short passages quoted by other ancient writers.

The list of lost books is followed by one of pictures, in which the vein of exotic fantasy becomes still more pronounced:

A delineation of the great Fair of Almachara in Arabia, which, to avoid the great heat of the Sun, is kept in the Night, and by the light of the Moon

An Ice Piece describing the notable Battel between the Jaziges and the Romans, fought upon the frozen Danubius

A Picture of the great Fire which happened at Constantinople in the Reign of Sultan Achmet. The Janizaries in the mean time plundring the best Houses . . . the Vizier riding about with a Cimetre in one hand and a Janizary's Head in the other to deter them

Some Pieces delineating singular inhumanities in Tortures. The Scaphismus of the Persians. The living truncation of the Turks . . . The exact method of flaying men alive, beginning between the Shoulders . . .

An exquisite Piece properly delineating the first course of Metellus his Pontificial Supper . . . together with a Dish of Pisces Fossiles, garnished about with the little Eels taken out of the backs of Cods and Perches . . .

Rare Chance Pieces, either drawn at random, and happening to be like some person, or drawn for some and happening to be more like another . . .

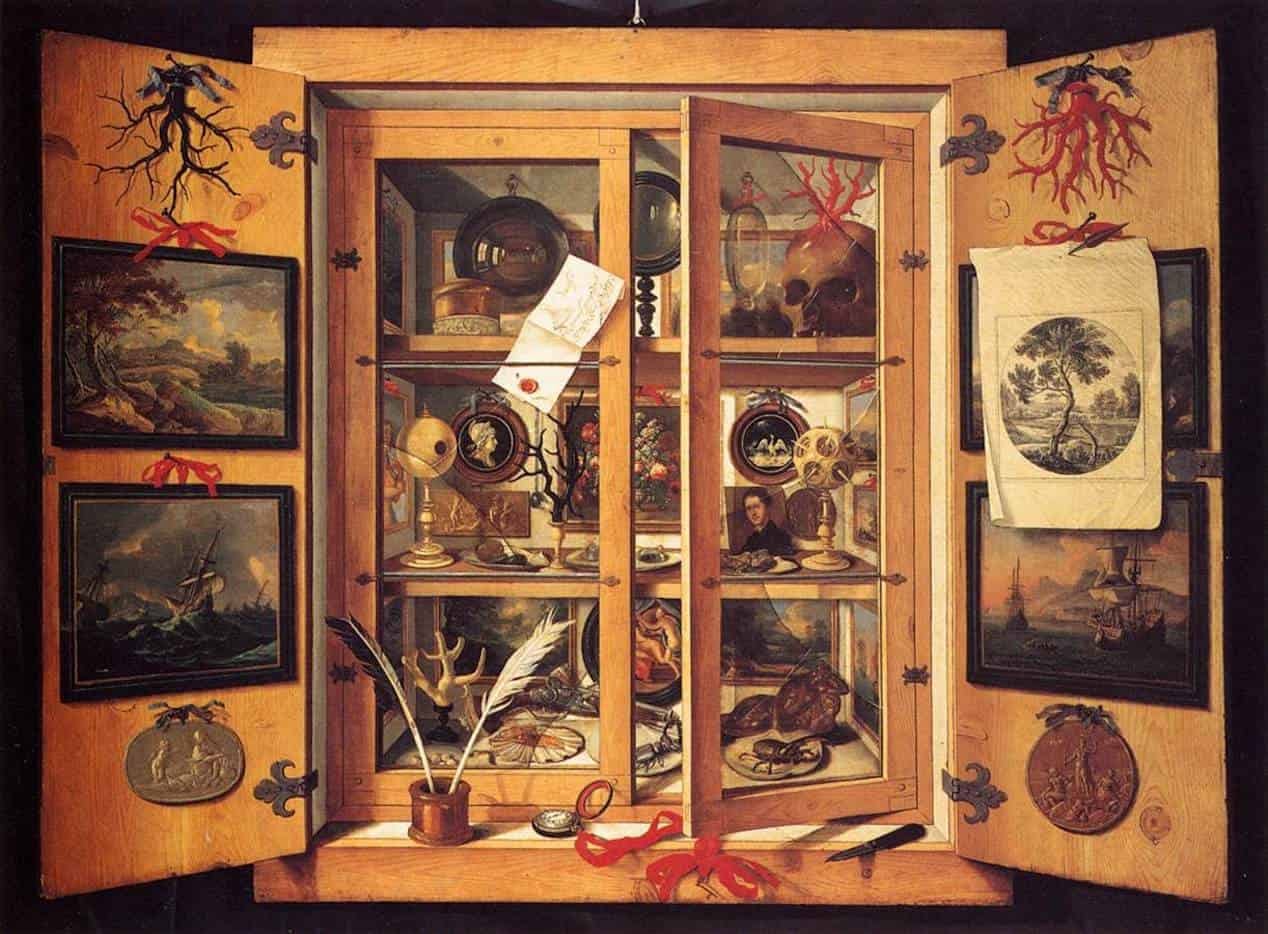

And finally there is a catalogue of ‘rarities of several sorts’, both natural and antiquarian, that seem somehow both preposterous and splendid. The list spoofs the late 17th-century craze for ‘cabinets of curiosities’ with their often improbable contents – while at the same time reflecting Browne’s own delight in strange facts and rare specimens.

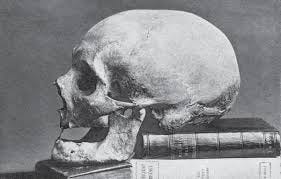

The complete Head and Body of Father Crispin, buried long ago in the Vault of the Cordeliers at Tholouse, where the Skins of the dead so drie and parch up without corrupting that their persons may be known very long after . . .

The Skin of a Snake bred out of the Spinal Marrow of a Man.

A Ring found in a Fishes Belly taken about Gorro; conceived to be the same wherewith the Duke of Venice had wedded the Sea.

Batrachomyomachia, or the Homerican Battel between Frogs and Mice, neatly described upon the Chizel Bone of a large Pike's Jaw.

. . . a Box which held the Unguentum Pestiferum, which by anointing the Garments of several persons begat the great and horrible Plague of Milan.

A Glass of Spirits made of Æthereal Salt, Hermetically sealed up, kept continually in Quick-silver; of so volatile a nature that it will scarce endure the Light, and therefore onely to be shown in Winter, or by the light of a Carbuncle, or Bononian Stone.

On the one hand we are reminded of Browne’s own Pseudodoxia Epidemica, a work gleefully exposing vulgar errors and popular superstitions. On the other, any dismay at human credulousness seems to be trumped by a deeper regret that these wonders are not to be found, and probably never were. The treatise ends abruptly, on a note at once wistful and teasing:

He who knows where all this Treasure

now is, is a great Apollo. I'm sure I am

not He. However, I am, Sir, Yours . . .

Although there is a subtle humour here, Browne the scientist and scholar seems genuinely haunted by the precariousness of human knowledge. What has survived from the past appears to be disturbingly arbitrary; yes, we have Homer and Plato, but given the precious things we have lost, isn’t this too much of a fluke to be much of a comfort? Indeed, were it not for the providence of God, might not the canonical letters of Paul have gone the same way as the letters to Seneca? And that is before we consider the unknown unknowns. In the Urn-Burial – his great meditation on human burial customs – Browne wondered subversively ‘whether there be not more remarkable persons forgot than any that stand remembered in the known account of time’; the Musaeum Clausum raises the same doubt about works of art and intellect. We cannot begin to know what we have lost.

Large are the treasures of oblivion and heaps of things in a state next to nothing almost numberless; much more is buried in silence than recorded, and the largest volumes are but epitomes of what hath been. The account of time began with night, and darkness still attendeth it. Some things never come to light; many have been delivered; but more hath been swallowed in obscurity and the caverns of oblivion.

That’s the Urn Burial again. Or sort of. Because the history of this unforgettable paragraph about forgetting makes the point quite as strongly as Browne’s formidable eloquence. For some reason Browne decided not to include it in his fair copy, and for centuries this marvel lay neglected in his papers (swallowed in obscurity and the caverns of oblivion); at some point a scholar picked it out, and eventually Browne’s modern editors restored it to the text. Some things never come to light; many have been delivered.

First published on the Dabbler blog in 2015 as part of Phantom Libraries, a series about missing, imaginary, or otherwise phantom books. The other parts are: 1. How to Have Sex in Texas, and Other Articles Deleted from Wikipedia; 2. Phantom Libraries: from Rabelais to Swift; 3. Phantom Libraries: from Dickens to The Sims; 5. The Unwritten Works of S. T. Coleridge; 6. The Dreaming; 7. Babel.

If you enjoyed this post, you might be interested in my ebook The Whartons of Winchendon —a short study of one of the strangest families in English history, featuring incest, treason, deep-sea diving, fairies, and the self-proclaimed Solar King of the World.